Part 1: Straight back down to Earth told the story of VTVL Rocket pioneers during the 1960s. In this second part of the story, a new set of circumstances set the stage for the reemergence of VTVL Rocket technology.

A new era of enthusiasm for space took hold under the Reagan Administration during the 1980s. It wasn’t born from a desire to explore new worlds or follow Kennedy’s Apollo era rhetoric, rather the new conservative agenda in America saw space as providing an new frontier for commercial pursuits…

Space factories could produce purer crystals and facilitate industrial processes impossible under the Earth’s gravity. New private space organisations could launch constellations of communications and Earth observation satellites and these in turn could be refuelled and refurbished in orbital space docks.

These new activities would be supported by two major NASA undertakings: The Space Transportation System – commonly known as the Space Shuttle, and Space Station Freedom. The Shuttle was now the national launcher for the United States, holding the promise of dramatically reduced prices for placing payloads in orbit. Flights would become so regular that it would be able to serve the commercial market alongside the needs of the Department of Defence (DoD – read more about military influence on the shuttle design) and NASA’s ongoing planetary explorations. It would also provide the means to carry the modular space station into orbit later in the decade. With Reagan forcing through legislation to enable the commercialisation of space, things looked set fair – but there were a few problems in the plan…

Even before the Shuttle took its first flight in April 1981 it was clear to many within NASA that the system would fall well short of the early promises of aircraft like operations and high flight rate. The Shuttle had been born into an era of budgetary constraint and its final design was a compromise reflecting that. In attempting to cater for many roles it fell short of achieving its potential and even more alarmingly the safety of the Solid Rocket Boosters (SRBs) and Thermal Protection System (TPS) were questioned. A RAND Organisation report commissioned by the DoD concluded that up to three of the orbiters could be lost during the operational life of the system and while such concerns weren’t widely circulated it quickly became apparent after the initial missions that the turnaround time between each flight would be counted in months not weeks and require thousands of engineers.

Against this background some entrepreneurs began to wonder if there was a place for free enterprise in the launch market as well as in orbit. One early entrant into this new field was Space Services Inc of America (SSIA) featuring the talents of Gary Hudson. As with other early adopters like Bob Truax (See more about Truax here) SSIA looked to create a vehicle that used technical simplicity to keep costs down and increase reliability. The expendable rocket Hudson designed, named Percheron, was of generally conventional construction but used pressure fed propellants removing the need for more complex turbo pumps. Unfortunately an engine test in 1981 led to an explosion and a consequent change of direction for SSIA towards solid propellants. Hudson decided to move on and rather than continuing with expendables he looked back to the work of Philip Bono and his Single Stage to Orbit (SSTO) designs of the 1960s.

Phoenix rises

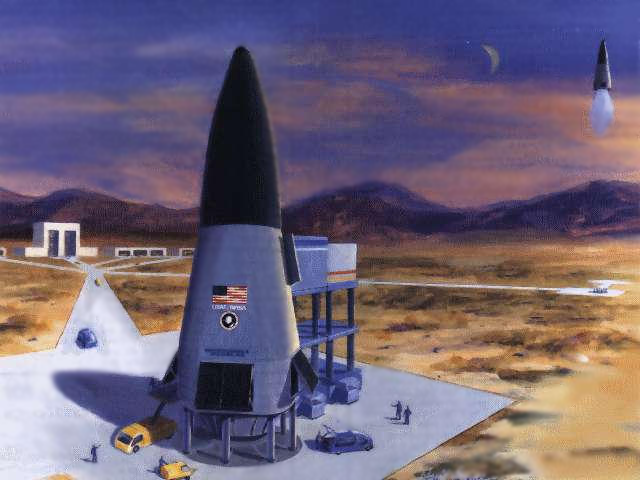

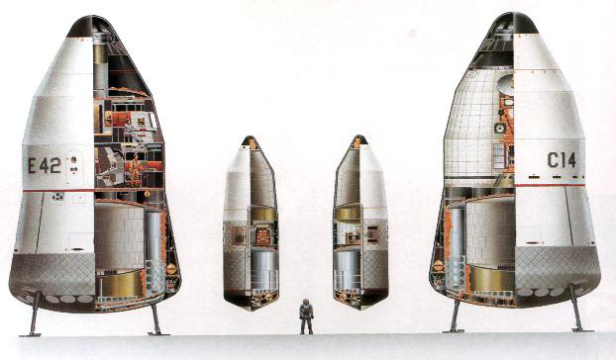

In 1982 Gary Hudson founded a new company, Pacific American Launch Systems, and began work on a series of vehicles under the name Phoenix. These craft were to be vertical takeoff, vertical landing SSTO rockets offering both crewed an uncrewed versions in a variety of sizes. The initial designs featured a large number of small rocket engines arranged around the craft’s heat shielded base and would use a dual fuel system of liquid hydrogen and propane with liquid oxygen as the oxidiser. The Phoenix would feature retractable legs for landing.

Throughout the mid 80s, the Phoenix designs evolved with later versions featuring a simplified liquid hydrogen/liquid oxygen fuel scheme and new propulsion in the form of Aeroplug nozzles which Hudson proposed as an evolution of the Aerospike nozzles featured in Bono’s designs. He also introduced a water based active cooling system for use during reentry again echoing the earlier Pegasus designs.

Hunter’s X Quest

Where Gary Hudson represented a new breed of rocket engineer, Max Hunter came from the heart of the Military Industrial Complex having cut his teeth at Douglas Aircraft prior to heading up their Thor IRBM missile programme. After leaving Douglas he worked for the National Aeronautics and Space Council, advising successive administrations on space policy before moving back into industry with Lockheed’s Missiles and Space Company (LMSC). Here he was instrumental in LMSC’s Phase A Shuttle proposal for NASA, the Star Clipper.

By the mid 80’s Hunter began to formulate his ideas into a concept he christened the X-Rocket. This would be a Vertical Takeoff Vertical Landing SSTO which relied heavily on automated systems for flight and vehicle checkout and engine-out abort reliability. The launch and flight would be overseen by a small crew and the design should require minimum refurbishment and checkout between flights. Standard sized payloads should be easy to load into the cargo section and fuelling operations should be quickly accomplished.

Hunter took this concept to LMSC who concluded it appeared feasible but when it was later assessed by Lockheed’s Missile Systems Division who mainly dealt with solid fuelled Trident missiles this opinion was reversed. Undeterred Hunter left Lockheed and decided to pursue his ideas independently.

A Space Truck for Star Wars

While Hunter and Hudson refined their SSTO rocket ideas, Reagan continued to expand his vision for space, this time beyond commercialisation and towards defence. Many conservative advisors saw the breakdown of the Nixon era detente and perceived a growing Soviet aggression following the invasion of Afghanistan. The old certainties of Mutually Assured Destruction and SALT treaties no longer looked so secure. Reagan initiated a huge increase in military spending and a large part of this went towards the vision of a space based missile defence shield which came to be known as the Strategic Defence Initiative or – more commonly – Star Wars.

The Strategic Defence Initiative Organisation (SDIO), set up in 1984 to design, develop and deploy the system would require frequent and reliable access to space for the constellations of sensor and killer sats envisioned. SDIO became interested in alternative forms of space access and were involved from an early stage with the DARPA Copper Canyon, later X-30 NASP, programme (For more on the X-30 NASP story see here). Following the Challenger disaster in January 1986, the SDIOs need for secure access to space became even more acute and it appeared NASP may not be the answer to their needs.

Help from the High Frontier

Concurrent to these developments a number of small non-governmental space interest groups began to coalesce around the idea that new, sustainable forms of space access could help secure American superiority in space. One of these groups was High Frontier headed by Lt. Gen. Daniel Graham, an influential figure in Washington and a leading advocate of SDI, particularly the concept of small independent kill vehicles which became known as Brilliant Pebbles. Also active around the same time was the Citizens Advisory Council on National Space Policy, a loose collection of aerospace professionals, military officials, sci-fi authors and ex-astronauts amongst others.

These groups were an eager audience for the ideas of Hudson and Hunter and they quickly began to champion the X-Rocket concept. Graham, Hunter and Hudson worked together to build a compelling case for the vehicle which now became known as Spaceship Experimental (SSX). Figuring that an SSTO of this type would be ideal for rapidly and regularly deploying smaller payloads such as Brilliant Pebbles they saw SDIO as a natural home for the project rather than either the Air Force or NASA where a bias towards existing projects might see SSX stifled. As the decade drew towards a close, the Reagan administration gave way to George H. Bush and his vice president Dan Quayle. As was traditional, the vice president assumed a leading role on space policy and Quayle was eager to reform NASA and encourage new initiatives. Graham used his influence to obtain an opportunity to pitch SSX to Quayle and stress its suitability for SDIOs needs. From this meeting, the group were able to get the concept assessed with a view to an experimental project being commissioned.

With NASP foundering under the weight of technical issues and unrealistic expectations, the SDIO were willing to examine SSX as an alternative and with their ‘smaller, faster, cheaper’ ethos the organisation did indeed seem like the most promising home for the project. So began the project which led to the DC-X.

The Delta Clipper takes shape

Envisioned as a 3 phase process, Phase 1 would see responses to the SDIOs requirements from number of contractors. Phase 2 would see a contract awarded for an experimental prototype to prove key operational and vehicle concepts and integrate some of the new materials and manufacturing techniques trickling across from the NASP and SCIENCE DAWN. The final phase would result in the creation of the full-scale SSTO vehicle. While Phase 1 didn’t exclude winged designs, it was felt that a VTVL rocket would best suit the requirements. The successful contractor moving forward into Phase 2 was McDonnell Douglas, offering a nice symmetry – Douglas having been one of Max Hunter’s previous employers and the home of Philip Bono’s innovative SSTO concepts. In a further nod to the past the vehicle became known as the DC-X, Delta Clipper recalling Douglas’s Thor/Delta rocket heritage and the Clipper boats that had done so much to establish commercial sea traffic – a feat the SSTO planned to replicate in orbit and X for experimental.

Even before the vehicle reached flight status, the programme was already under threat as the end of the Cold War had brought the need for SDI into question. As the SDIO became less able to justify their need for a launch vehicle, there seemed no obvious alternative home for the DC-X. NASA still had the Shuttle as well as NASP and the proposed National Launch System (NLS) on the horizon. There seemed little appetite to pursue a small reusable launch vehicle project.

Eventually sufficient funding was found to allow initial flight testing and on 18th August 1993 the DC-X took to the air on a 1 minute hop to test the flight control and landing systems. DC-X flew twice more in September 1993 at which point the initial SDIO funding ran out, once again plunging the programme’s future into doubt.

Political struggles

Much of the story of the DC-X was played out not at White Sands, but across the continent in the White House. In 1992, the final year of the Bush administration, Dan Goldin was brought in as the new NASA administrator. A former NASA employee, he aimed to apply what he’d learned during his time at TRW to create a new leaner agency under the maxim ‘Faster, Better, Cheaper’.

In 1993 Bill Clinton took over the Presidency and his administration set about a number of reforms to existing space policy. Out went George Bush’s Space Exploration Initiative and its NLS. The X-30 NASP was also cancelled, still years and billions of dollars away from producing a flight article. New ideas were needed to keep NASA in the launch market post-shuttle and Goldin initiated the Access to Space study to examine the possible options. One strand of this Access to Space dealt with Reusable Launch Vehicles (RLVs) and led to the study of a baseline vehicle named X-2000.

The SDIO was also undergoing changes which led to a change in focus to ground launched missile interceptors and a change of name to the Ballistic Missile Defence Organisation (BMDO). There would no longer be a need, or indeed funding, for an SSTO launch capability but NASA’s new interest in RLVs seemed to point the way to the agency becoming DC-X’s new home. Frustrated by the hiatus in the flight test programme and the uncertainty surrounding the DC-Xs future, the groups who has been so instrumental in assisting Hunter’s X-Rocket in its early stages now mobilised again, this time with the added backing of New Mexico politicians and managers directly involved in running the project. This pressure eventually helped lead to a new funding arrangement whereby NASA and the Advanced Research Projects Agency (ARPA) jointly contributed to restart the flight tests.

This incident presented the programme with an opportunity – either the vehicle could be repaired to its original specification, or proposed improvements could be made. NASA had agreed to take on the DC-X programme and was eager to test new materials and components in support of its RLV initiative so the decision was made to upgrade the vehicle. A new aluminium-lithium alloy oxygen tank and composite hydrogen tank were installed and changes made to the flight control system. Some within the programme felt these changes were straying from the original SSX ethos and that the results as well as NASA’s project management did not in fact constitute improvements, but the revised vehicle – now named DC-XA – returned to White Sands to resume flight testing in 1996.

RLV becomes X-33

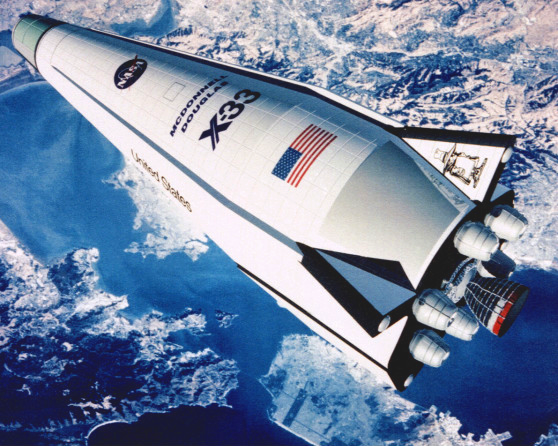

While the second set of DC-X flight tests had been progressing during 1994/5 NASA had become convinced that an RLV was now within their technological means and set about canvassing proposals from the aerospace industry for a technology demonstrator which, it was hoped, would lead to a fully re-usable SSTO vehicle early in the new century. This requirement came at a fortuitous time for the McDonnell Douglas DC-X team as it was by now obvious that no other government agency would be able to fund a full scale follow-on craft to the DC-X. Accordingly, they put together a proposal based on their original DC-Y follow on vehicle and were selected to progress through to Phase 1 of what NASA were now calling the X-33 programme.

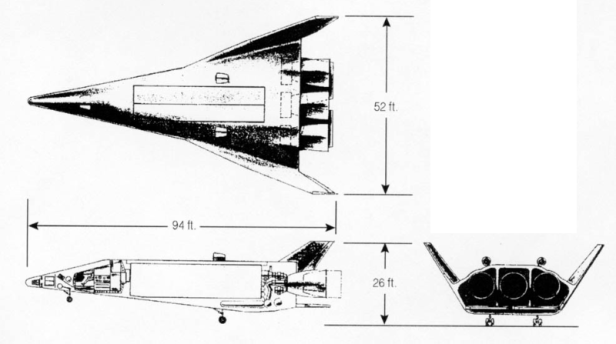

Their competitors at this stage were Rockwell International, who proposed a winged vehicle reminiscent of their shuttle orbiter and Lockheed Martin Skunk Works whose design was a flattened triangular lifting body (ironically echoing the Star Clipper Max Hunter had worked on in the late 1960s) using innovative linear aerospike engines. Given that they already had a vehicle flying that was a functioning embodiment of ‘Faster, Better, Cheaper’, McDonnell Douglas certainly appeared to have good grounds for optimism. The technologies being built into the DC-XA were the very ones that NASA hoped would give the X-33 the edge to prove the SSTO concept and as flight tests resumed in 1996 the media showed more interest in the DC-XA concept and its possible future applications.

The DC-XA made its first flight on May 18th 1996 and following this was re-christened Clipper Graham in memory of one of the programmes strongest proponents, Daniel Graham, who had died some months before. More flights followed with a 24-hour turnaround being demonstrated between the June 7/8th missions. The second of these flights set programme records with a peak altitude of 3140 metres and had a duration of 142 seconds. Sadly the next flight ended in disaster for the DC-XA as, after an 140 second flight on July 31st, one of the four landing struts failed to deploy and the vehicle tipped over after landing causing an explosion which damaged it beyond repair.

The cause of the accident that destroyed the DC-XA was a disconnected hydraulic line on the landing strut – an item that should have been picked up during pre-flight inspections. This error could have been seen as an indictment of the ‘Aircraft-Like Operations’ approach, but some within the programme pointed to the low morale now surrounding the programme as a probable cause. By now, the decision on the prime contractor for the X-33 programme had been made by NASA and the decision had gone the way of the Skunk Works.

As future events would prove, their design proved too ambitious depending as it did on many breakthrough technologies. For the X-33 ‘Faster, Better, Cheaper’ proved to be anything but (For more on the story of the X-33, see here). For the Vertical Takeoff, Vertical Landing SSTO rocket it looked like a case of wrong time, wrong place and a return to the wilderness, but the many successes of the DC-X had not gone unnoticed by a new group of tech pioneers, then beginning to amass their fortunes via the emerging world of the Internet.

Part 3 of this article can be found HERE

Author’s Note

For this part of the story of VTVL SSTOs I’ve drawn heavily on Andrew J. Butrica’s excellent Single Stage to Orbit: Politics, Space Technology and the Quest for Reusable Rocketry. I fully recommend this to anyone interested in understanding more about the political context surrounding the DC-X – what I have provided above is merely a brief summary of these events.

Sources

Single Stage to Orbit: Politics, Space Technology, and the Quest for Reusable Rocketry – Andrew J. Butrica

History of the Phoenix VTOL SSTO and recent Developments in Single-Stage Launch Systems (1991 report) – Gary C. Hudson

Exploring Future Space Transportation Possibilities – Ivan Bekey

Single-Stage-to-Orbit – Meeting the Challenge (1995 report) – D.C. Freeman, T.A. Haley, R.E.Austin

Black Day at White Sands – Preston Lerner, Air & Space Magazine, Aug 2005

Critical Issues in the History of Spaceflight: Chapter 9 “A failure of National Leadership” Why no replacement for the Space Shuttle – John M. Logsdon

Space Shuttle: The history of the Space Transportation System – Dennis R. Jenkins

Secret Projects: Military Space Technology – Bill Rose

The Space Shuttle Decision: NASA’s Search for a Reusable Space Vehicle – T.A. Heppenheimer

Facing the Heat Barrier: A History of Hypersonics – T.A. Heppenheimer