On August 22nd 1963 high above Smith Ranch Dry Lake in Nevada, NASA pilot Joe Walker dropped away from the NB-52 carrier aircraft in X-15 number 3. In the seconds that followed he successfully ignited the research plane’s powerful XLR-99 rocket engine and pulled back on the side-stick, aiming for the darker skies above. Three previous attempt to get this flight – the 91st of the programme – launched had been scrubbed for various reasons, but today everything had worked fine and the X-15 soon streaked upwards leaving the NB-52 and chase planes in its wake.

Joe Walker had originally joined what was then the NACA High-Speed Flight Research Station at Edwards AFB in 1951 and had flown many of the early X-Planes as well as the Air Force’s Century Series jet fighters. He became the centre’s Chief Research Pilot and in 1958 was selected as an astronaut candidate for the Air Force’s Man In Space Soonest (MISS) programme. When MISS came to nothing following the formation of NASA which then took responsibility for the nation’s early manned spaceflight efforts under Project Mercury, Walker continued his career at the newly renamed Flight Research Centre (FRC) and was named as NASA’s chief project pilot for the X-15 making the first NASA flight of the research aircraft in 1960. Following Flight 91, Walker would be retiring his seat in the X-15, but his final flight would quite literally see him leaving on a high.

The planned maximum altitude for the flight was 360,000ft. Engineers and flight planners at the FRC had calculated that the X-15 could be capable of altitudes up to 400,000ft but there was less confidence that a reentry could be safely flown from this altitude so a 40,000ft safety margin had been adopted – an amount that could easily get eaten up should the pilot be a degree off in his climb angle or the engine was shut down a second late or produced more than the expected thrust. On a build up flight for the maximum altitude attempt on the 19th July these factors had conspired to send Walker 31,000ft beyond his target altitude to a maximum 347,800ft (65.8 miles) – the safety margin was clearly a prudent measure. Today Walker was aiming for the safe maximum the X-15 could achieve…

As the engine shut down Walker still had nearly two minutes of climb ahead of him as the X-15 carved its huge ballistic arc across Nevada and California on its way to Edwards AFB. The peak altitude was slightly lower than planned, coming in at 354,200ft (67.08 miles) but Walker experienced a few minutes of the weightlessness so familiar to his Mercury counterparts until the reentry began and gravity re-established its grip, reaching a maximum 5g as Walker pulled out of the steep descent. Having successfully glided the X-15 back to Rogers Dry Lake, he landed safely some 11 minutes and 8 seconds after launch. Joe Walker had completed his 25th and final X-15 flight and in doing so become the first person to enter space twice. As a NASA employee rather than a military pilot ‘on loan’ to NASA or a member of the Soviet Air Force, he was the first civilian to enter space. Flight 91 also marked the last occasion on which NASA sent a vehicle with a single occupant beyond the 100km (62 mile) Kármán line – the internationally recognised boundary of space as defined by the Fédération Aéronautique Internationale.

Given that space fever had gripped the United States following the flights of Project Mercury, you might be forgiven for thinking that Walker’s next flight would be to the nation’s capitol for a ticker tape parade and a meeting with the President. At a time when the United States was battling the Soviet Union for space firsts, Walker’s achievements would seem to have provided a propaganda victory and be a cause for national pride and celebration, but that proved not to be the case.

In NASA’s eyes Walker was a pilot not an astronaut. To be a member of the NASA astronaut corps meant being either one of the original Mercury 7 or the second group of 9 (including Walker’s former colleague and fellow X-15 pilot Neil Armstrong) recently selected in anticipation of the upcoming challenges of Gemini and Apollo. There would be no nationwide celebrations for Walker’s achievements, in fact on the contrary NASA’s official biography of Walker mentions neither the word ‘space’ nor ‘astronaut’. The space agency later credited Gus Grissom as being the first two-time space traveller following his Gemini 3 flight in March 1965. The honour of final solo NASA flight was granted to Gordon Cooper for his Faith 7 flight some months before Walker’s flights. As for the first civilian in space? That title is still a matter of dispute but often bestowed upon Neil Armstrong for his Gemini 8 flight in 1966.

For Walker there would be no lucrative LIFE magazine contract, no souped-up Corvette provided by a friendly local dealer, just regular government pay and a new project to move onto. Things moved fast at the FRC during the 60s and Walker had the Lunar Landing Research Vehicle and the Mach 3 XB-70 bomber programmes approaching. Over the course of the X-15 programme, Walker saw his Air Force counterparts who flew the X-15 beyond a 50 mile altitude receive their astronaut wings (Air Force rules recognised the 50 mile boundary as opposed to the 100km Kármán line). It isn’t recorded what, if any feelings, he expressed about NASAs decision not to grant him a similar award. He just continued his long career in the service of the NASA FRC.

Tragically Walker would lose his life in the skies above the Mojave on June 8th 1966. Given the nature of much of the flying he did for NACA/NASA it seems especially ironic that he should lose his life during a photoshoot, but during a formation flight of General Electric powered aircraft to gather publicity shots for the company Walker’s F-104 tailplane collided with the XB-70’s lowered wingtip causing Walker’s plane to flip over the bomber in the strong vortices and explode destroying the bomber’s vertical tails. Walker was killed instantly on impact with the huge bomber, XB-70 co-pilot Carl Cross was also killed when unable to eject from the stricken XB-70. The photoshoot had not been officially authorised and cost the careers of some Air Force officials who had given the go-ahead for it to take place. At the time of his death Walker was in training to become NASAs project pilot on the XB-70. Joseph A. Walker was buried in nearby Lancaster, never leaving the Mojave that had been his home and workplace for so long.

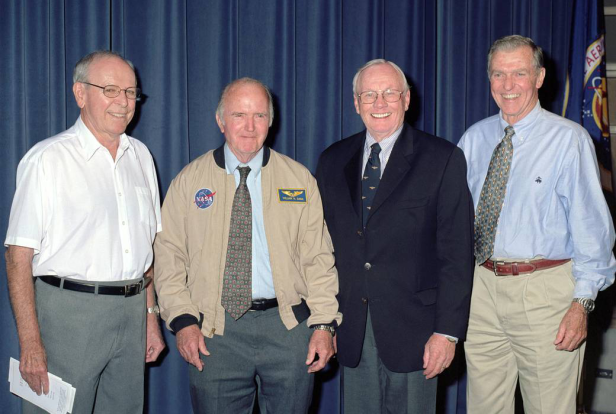

Some official of recognition for Walker’s achievements finally came, albeit over four decades late. Following significant lobbying by aviation historians Dennis R. Jenkins and Tony Landis, authors of HYPERSONIC, a fantastically detailed history of the X-15 programme, NASA finally relented and on August 23rd 2005 Walker and fellow NASA X-15 pilots Jack McKay and Bill Dana were awarded their astronaut wings.

Regarding the posthumous award of astronaut wings, Walker’s son Jim said:

“My dad’s an astronaut, to our family it means a lot. We are grateful. As my brother mentioned, our father probably would be humble because he knows it was a group effort and it was all the people in the X-15 program and all the people down the line. These are the real heroes.”

Walker’s unofficial altitude record set on X-15 Flight 91 remained unmatched until October 4th 2004 when pilot Brian Binnie took SpaceShipOne to 367,500ft on its third and final qualifying flight to claim the Ansari X Prize.

If you’d like to read a fuller account of the X-15 programs, please take a look at my three-part overview here:

Part 3: The Final Steps and Legacy

Sources

HYPERSONIC: The Story of the North American X-15 – Dennis R. Jenkins & Tony R. Landis

VALKYRIE: North American’s Mach 3 Superbomber – Dennis R. Jenkins & Tony R. Landis

The X Planes: X-1 to X-45 – Jay Miller

At The Edge Of Space: the X-15 Flight Program – Milton O. Thompson

A Long Overdue Tribute – Jay Levine, NASA Dryden X-Press article (Oct 21st 2005 – accessed May 22nd 2017)

Joseph A. Walker – NASA Biography (Updated March 2nd 2016 – accessed May 22nd 2017)

Apollo 1 Crew Biography: Gus Grissom – Mary C. White (accessed May 22nd 2017)

The last thing anyone wants is a Nasa award.

LikeLiked by 1 person

So Walker was technically the first man ever to enter space and experience “true” wheightlesness.

LikeLike

How are you defining true weightlessness? I’m not sure the weightlessness he experienced was that different from what Shepard and Grissom experienced on the 2 suborbital Mercury flights

LikeLike

I may be wrong but I assumed that Walker did his flight before those Mercury flights.

LikeLike

His to flights above 100km were both after Cooper’s Faith 7 flight, the final Mercury mission. There had been earlier X-15 flights beyond 50 miles, and Bob White had earned his USAF Astronaut wings for these, but Mercury exceeded the Karman line first.

LikeLike

He was the first human to cross the Von Karman line (100,000 meters) twice. Did it 34 days apart.

LikeLiked by 1 person

“Von Karman?” where did the Von come from?

LikeLike

Not sure of the exact derivation of the ‘von’ in Theodore von Kármán’s name – generally in Germanic languages it tends to denote nobility, or can simply mean ‘of’ but no idea if this is the same for Hungarians.

LikeLiked by 1 person

It was my own problem. I inadvertently stuck in “Von” when it shouldn’t be there. I was pointing out my own error.

LikeLike